Australia is embracing an ageing population and an increasing percentage of that population who have chronic disease. This is putting significant strain on the health system, which is now facing massive workforce shortages. Approximately 11 per cent of the total workforce of Australia is engaged to some degree in the health industry, forming one of the largest groups in the community. Considering the demands, an increase in that percentage to around 20 per cent of the total workforce is needed by 2025. We are not going to do this by increasing doctors and nurses alone. We have to look at a paradigm shift in how we deliver the services, how we emphasise health promotion and disease prevention and how we provide the community at large with some skills to take care of themselves.

The health workforce of the future will need to be more flexible and mobile and its workers will need to be multi-skilled. The workforce shortages currently affecting Australia in nursing, medicine and the allied health professions are also seen in other overseas jurisdictions and this will make recruiting health professionals much more difficult and expensive than in the past. For years a number of Government instrumentalities have concluded that the existing medical workforce is adequate for our future needs. Interestingly, medicine is still the only University course where numbers are controlled by the Federal government.

A number of factors have impacted on these shortages including the feminisation of the medical workforce, changing work patterns including safe hours ‘recommendations’ and the globalisation of the health workforce. The changing gender mix in the medical workforce has played a significant role in this crisis with women wishing to work shorter hours and having significant periods of time off for their families. These work aspirations are now being taken on by male doctors as well. Within medicine there are particular challenges for training, as increasingly medicine and particularly surgery are being carried out primarily in the private sector. Doctors who undergo almost all of their training on the ‘public purse’ have the opportunity to provide entirely to the private sector once they have achieved their specialist qualification.

We need to review the contribution of the private sector to training. One idea would be to require all specialists to provide a certain number of sessions to the public sector – and be paid for them — for a period of 10 years after attainment of their specialist qualification. There is a significant discrepancy in financial reward between the public and private sectors which must be addressed. This discrepancy is made worse by the emphasis in the Medical Benefits Schedule on payment for procedures. There is little doubt that this has been a disincentive for young doctors to go into general practice or some of the non-procedural specialties, while interventional cardiology, gastroenterology and surgical specialties are very popular. This issue of remuneration of doctors was addressed some years ago by a relative value study but sadly never acted on by Government. The relative value study has been reactivated by the recent Productivity Commission Draft Report. Recommendations for revisiting the relative value study should be strongly supported in the final document as it is not sustainable to have the ‘cognitive’ part of medicine rewarded so poorly in relation to procedures.

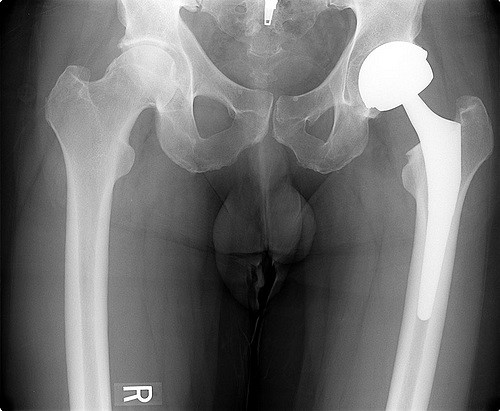

Another issue is looking at alternative strategies for care delivery. For example, pharmacists could be involved in routine prescribing of repeat prescriptions and medication monitoring. Appropriately trained radiographers could read x-rays as well as radiologists. Pathology technicians currently carry out routine screening for cervical pathology and this could easily be extended to cover some diagnostic work including involvement in routine histopathology screening. Nurse practitioners could be involved in chronic care (limited prescribing and some procedures) and, along with physician assistants, could be involved in procedures such as colonoscopy, minor surgery and anaesthetics. And physiotherapists could perform triage for musculoskeletal injuries in the Accident and Emergency Departments of our busy hospitals.

A key benefit is that this would ‘liberate’ those workers being substituted to focus on much more important, interesting and remunerative issues. For example, routine x-ray reading by radiographers allows radiologists more time to carry out angiography or to insert stents.

Although nurse practitioners have been trained in this country for over a decade there are still very small numbers (less than a hundred) who are working as nurse practitioners in the community. Issues of career development, remuneration and indemnity need to be sorted out by State and Federal Health Authorities.

We should also be developing a new range of new health workers – physician assistants for example. In the United States there are some 60,000 physician assistants who grew out of the ‘medics’ returning from the Vietnam War. These professionals are trained in over a hundred programs across the United States, the majority being associated with medical schools or health science faculties. These programs run for approximately two years duration and involve training in basic sciences as well as clinical aspects. Physician assistants in the United States take on a range of activities from primary care to involvement in a number of specialty areas such as orthopaedics, critical care, gerontology, management of chronic disease, sports medicine and anaesthetics.

The recent draft report of the Productivity Commission into the Health Workforce offers a number of suggestions and we must ensure that when the final report comes out it is acted on.

Suggestions include the creation of an Advisory Health Workforce Improvement Agency – linking the funding for delivery of health professional training programs much more closely with the workforce requirements and health departments; similarly, the establishment of an Advisory Health Workforce Education and Training Council to link health education and workforce. State health departments should be encouraged (required) to take on a responsibility for training and research. This could be done through the Medicare Agreement where the responsibility for States to provide the clinical training aspects of all health professionals could be legislated.

There needs to be much more transparency in the funding of training and an opening of opportunities for alternative pathways. Up until now postgraduate training has been the total purview of the Colleges. Although this training is to a high standard there have been concerns about restrictions on numbers in some of these training programs. There is also a view from the Colleges that much of this training is provided ‘pro bono’ by College Fellows. If one looks carefully, it is clear that the majority of time provided for training is remunerated through sessional payments or salary through a state health department or university.

There should also be significant opportunities for other health professionals to gain access to the Medical Benefit Schedule. For example, recent access was granted to exercise physiologists, who can be extremely useful in providing exercise programs to reduce weight and help diseases such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease or arthritis. The Report proposes an independent group much like the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme to look at the Medical Benefit Schedule and assess its effectiveness.

In addition to the findings of the enquiry, new technologies such as e-health or telemonitoring must be considered. These technologies can help in delivery of services in rural Australia, and in assisting continuing health education programs through e-education.

It is time Australia got serious about the broad public health agenda and funded it appropriately.

The most important thing that the Productivity Commission Report might do is to stimulate a debate that is long overdue in this country about what the community wants from its health system and how much it is prepared to pay for it.