From the patient’s point of view, Australia’s health system should be seamless. It should be designed around patients’ needs, free of the legacies of historical divisions. Instead, the patient requires great skill in navigating the plethora of disconnected programs. The design of our health arrangements is structured around provider interests and funding sources. While governments have rhetorically abandoned input-based funding, in health care it still reigns supreme.

| [adsense:234×60:1:1] |

Transforming our health system to focus on the patient would require structural and design changes at both commonwealth and state level. It doesn’t mean spending more money. Australia wastes a lot of money in health. We spend 10 per cent of the GDP per annum on health, double the amount spent in the 1960s. Part of the reason for the increasing costs faced by patients is that present inefficient health arrangements are coming to the end of their design life.

When health professionals have worked within the same industry for most of their lives with great dedication, they find it difficult to pinpoint its weaknesses. There is a Polish proverb that says, ‘the guest sees in one hour what the owner of the house does not see in a lifetime’. In the same way, the insight of patients can reveal more about the health industry than those working within it.

You don’t have to be Einstein to see that structural changes need to be made. But so often the political response is to placate providers rather than direct the system to the community and patients.

Let us look briefly at the current structure of health arrangements:

- We have highly institutionalised and hospital-centric health arrangements, even when it is obvious that the autonomy and interest of the patient is best served by home-based or local health services

- There is overwhelming emphasis on medical intervention by providers and too little on keeping people healthy in the community. Over 90 per cent of health funds are for medical services.

- There is a lack of integration and co-ordination between programs. This goes beyond the problems of Commonwealth/state divisions. Even within the Commonwealth, for example, the Pharmaceutical Benefit Scheme (PBS) and Medical Benefits Scheme (MBS) are run as different programs with different criteria relating to safety nets and co-payments.

- The Commonwealth government is concerned about the growth in pharmaceutical costs but very often pharmaceuticals can reduce costs in other parts of the health system and the wider economy for the benefit of the patient.

- Our health arrangements are increasingly based on medical specialisation; while patients are seeking more holistic care. With a confusing and neglectful mainstream health system, it is not surprising that more and more of us look for alternate therapies.

- There is little coherence in workforce planning. Professionals are trained and work most of their lives in professional units without assessing the overall perspective of who they should all be serving together, the patient.

|

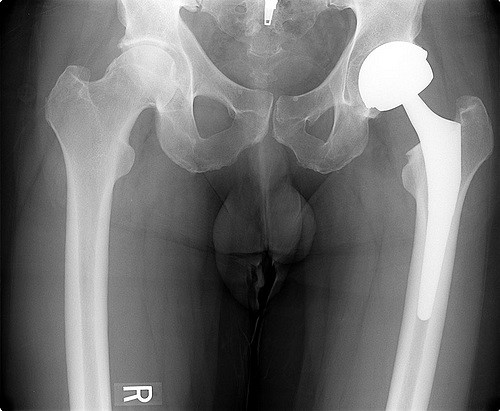

| Image from sxc |

What can be done to change our health structure and design to put patients and the community at the centre of the system?

- There should be a joint Commonwealth/state health commission with appropriate governance, coverage and pooled funding in each state to administer all major health services. It would happen on a state by state basis and not depend on a largely unlikely and unachievable nation-wide agreement. A patient doesn’t give a hoot who provides the service or how it is funded. What matters to the patient is their health, the availability of quality service and its efficient delivery.

- In the longer term, the simultaneous elections for commonwealth and state parliaments could encourage political parties to co-ordinate and lobby for their programs across the Commonwealth/state divide.

- Within that Commonwealth/state combined jurisdiction, services and funds must be delivered in regions on a needs-adjusted population basis.

- Wherever possible, services should be delivered by the smallest or the health authority that best services the patient and their community. Of course many issues are better handled nationally, particularly when dealing with standards and the concentration of bargaining power against powerful provider interests, as is the case with pharmaceuticals. However, the important principle of subsidiarity is localising health care. It is essential that we bring delegated authority and delivery as close as possible to the patient.

- A network of primary care and multi-disciplinary community health clinics across Australia is needed. The Centre for Policy Development‘s Policy portal is working on such a plan. Watch this space. At the moment we envisage about 200 such centres across Australia initially, based on average catchment population of about 100,000 people, with adjustments for remote and smaller communities. The centres would be based on divisions of general practice in most instances and would be mainly privately run. The coverage, governance and costs of such centres are now being explored.

- The evidence is clear that countries with strong primary care have lower overall costs and generally have healthier populations, especially where there is higher primary care physician availability. Greater availability to primary care physicians also reduces the adverse effects of social inequality.

- The training and employment of our health workforce, despite its great professionalism and dedication, weighs heavily against the patient-centred health system. The Centre for Policy Development‘s Policy portal is working on a supplementary policy paper on workforce issues. It will highlight the need for radical restructuring of the workforce and work systems, not just ensuring more staff to do the same things the same way.

- The long-awaited unique patient record will also enable a holistic outlook of the patient, drawing together information from a range of clinicians and jurisdictions — both Commonwealth and state, public and private.

- We need health ministers to assume leadership in the interests of patients and their health in its wider sense, not just be ministers for health care programs. The biggest cause of poor health and premature death is poverty. Education, childcare, employment, spatial planning, housing, immigration and trade (eg the Free Trade Agreement with the US) all affect the health of a community and the individuals within it. We need a Health Minister with the authority of the Treasurer to be concerned with more than health care programs.

- Finally, countervailing power is needed to challenge the domination of the debate and health resource allocation by powerful provider interests. My experience is that when the community is well informed, its views are very different to what the media portrays as important issues. Hospitals and waiting lists are really the symptoms of other problems. Informed community views about priorities invariably put mental health and Aboriginal health at the top of the list. So, community and patient engagement through models such as citizens’ juries is essential. Without taking the decision-making role away from ministers, community engagement can better inform ministers when making decisions about priority spending. The Centre for Policy Development will also be releasing a supplementary policy paper on community engagement and countervailing power on behalf of patients and the community.

We need design change, not incremental reforms. We need to win the political debate that a patient-focused health system is essential for efficient and quality care. Hopefully it will then be easier for ministers to make the political decisions necessary. The key is political will.

This is an edited version of a speech delivered to the Australian Health Care Association National Congress, Brisbane, 9 November