CHRIS BONNOR published in The Guardian

19 February 2018

Layers are being created within and between Indigenous communities, making closing the gap ever more difficult

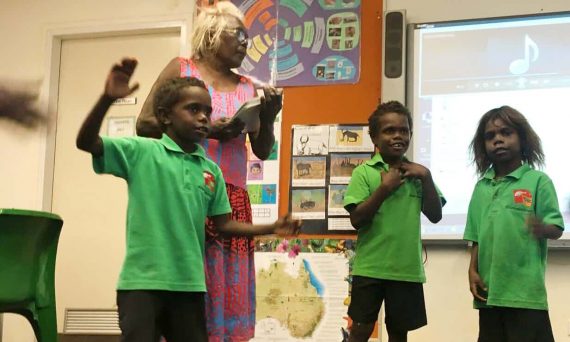

Most Indigenous children attend schools well down the socio-educational ladder. Photograph: Helen Davidson for the Guardian

We are now into the tenth anniversary of the strategy to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia. Last week saw a report on progress, a subdued celebration on scattered achievements and copious hand-wringing over endemic failures.

It seems that amongst the Closing the Gap target areas it is school education where some celebration is justified – with some gains in numeracy, reading and school retention. There is still a long way to go but any progress will be a welcome boost for schools more used to wearing all the blame for low levels of student achievement.

Indigenous education has more than its share of set-backs but we also hear about heroic efforts by teachers to turn the numbers around. The work done by Chris Sarra and the Stronger Smarter Institute is deservedly well-known. Many schools are stand-outs and new learning designs are challenging what schools should do, and what success should really look like.

But alongside our efforts to close the gap our school system operates in a way which keeps it as wide as ever, in the process almost mocking efforts at the school level. Most concerning is how we are consigning most Indigenous students, especially the strugglers, to the schools with the least capacity to address their pre-existing disadvantage.

These are the schools at the bottom end of the school socio-educational (SEA) ladder which we have created in Australia. It is a regressive hierarchy, affecting the disadvantaged in general but very visibly so with most Indigenous students. We are now creating layers within and between Indigenous communities, just as we are with other Australians. Those who can will scramble up the ladder; those who can’t will struggle – increasingly in a class of strugglers, a class of their own.

How does this play out on the ground? Schools with students who are advantaged accumulate the social, cultural and even financial capital of their supportive and resourceful parents. Schools which enrol an increasing proportion of disadvantaged students gradually lose the resource of higher-performers and role models. Teacher experiences and expectations, as well as curriculum offerings and access, can change and resources might be scarce. Teachers increasingly have to consolidate skills and knowledge already traversed. The odds against making the much-needed breakthroughs mount up.

This is what we are especially doing to Indigenous students. Most attend schools well down that socio-educational ladder: lower SEA government and Catholic schools and some remote Independent schools. The government schools face the biggest challenge because the two private sectors enrol the more advantaged from Indigenous communities. As always, some students emerge as winners and the schools can sometimes tick an equity box, while compounding bigger problems elsewhere.

There are urban-regional contrasts: the trend to residualise Indigenous students is magnified in regional areas where a majority of them attend school. The most disadvantaged regional schools continue to have high Indigenous enrolments. The reality for these schools is that there is no one below them on the school ladder. They don’t win the more advantaged students from the higher rungs and must accept anyone on the way down.

This is also more noticeable outside the cities because the successful and the strugglers live almost side-by-side, but their children often go to very different schools. Centres such as Coffs Harbour, Orange, Tamworth-Gunnedah and Wagga Wagga offer a considerable choice of schools. What is sometimes a black-white divide is not so much a matter of active discrimination; it is the level of school fees which sorts everyone out. There are very few Indigenous students in Anglican schools, more in community Christian, Catholic and higher SEA government schools – but most are in other government schools.

While an experience of schooling is shared by all, Indigenous and non-Indigenous children increasingly don’t share the same school. Closing this gap needs to be part of the obligation of every school: we will only do it if we increase the number and proportion of our schools which are obliged to be open to children from every family in every circumstance in every part of Australia.

It seems that concerns about slow progress towards targets have triggered an overhaul of the Closing the Gap strategy. They will reshape the targets, maybe broaden their reach, widen the consultation and be happy enough with a job well done. Little will change unless they come to grips with a framework of schools intent on widening the gaps.

- Chris Bonnor is a Fellow of the Centre for Policy Development and a director of Big Picture Education Australia.