Published in The Australian on 13 July 2020

Victoria’s decision to give private security contractors responsibility for quarantine hotels is the subject of a judicial inquiry, which will reveal the true cost of this decision and whether it was right. But the reported poor performance of those contractors suggests that we should consider government reliance on such outsourcing more generally.

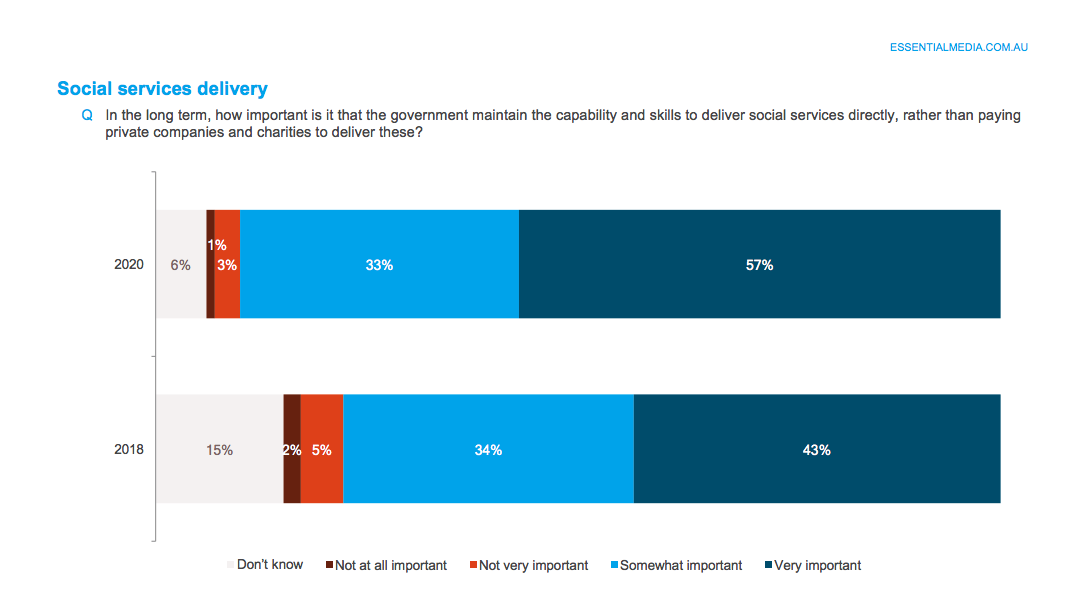

Australians are uneasy about outsourcing essential services. The Centre for Policy Development examined attitudes to democracy and the role of government and service delivery in 2017 and 2018. Australians believed services delivered by government were higher quality and more affordable, accessible and accountable than those delivered by private companies or charities. Three in four thought it was important for government to maintain the capability and skills to deliver social services directly instead of paying others to do it.

Last month, we asked the same questions again. The result was striking. Nine in 10 now think it important for government to maintain the capability and skills to deliver social services directly. The view was emphatic regardless of voting intention, although Coalition voters were more in favour.

This isn’t about hotels. It’s about who you trust to deliver when the outcome matters much more than profit — when your life might depend on it. Recent history hasn’t been good for outsourced services. The aged care royal commission stated it is “a myth that aged care is an effective consumer-driven market”, and it slammed the system for too often neglecting older Australians

The biggest mountain Australian governments need to climb now is the issue of jobs, yet our national employment services system, Jobactive, is all outsourced. Its caseload grew from about 615,000 at the start of 2020 to almost 1.4 million by the end of May. And that’s before JobKeeper finishes.

Australia should boast the world’s best employment services system after three decades of uninterrupted economic growth. But a 2018 review led by Sandra McPhee found our system had to do “much better”. Case managers averaged 148 clients. Providers were in touch with only 4 per cent of employers. The system was pre-digital, designed for a world without Google and Seek. It wasn’t cheap either, costing about $1.3bn a year.

With so much to fix, contracts with job service providers were extended to 2022 just before last year’s federal election. Trials started of a new digital model and specialised wraparound services for the most disadvantaged jobseekers. Today the system is overwhelmed.

We should have moved faster. Climbing the jobs mountain with Jobactive will be like doing the Tour de France on a bike with a single gear.

Noel Pearson has called for a government jobs guarantee due to COVID-19 and for this to be co-ordinated by local governments. There is merit in exploring this. Many local government authorities are highly effective. Those able to deliver should be given an opportunity to demonstrate their capabilities in solving problems critical to their communities, with local accountability and more sophisticated funding systems.

The need for local approaches that tap into community networks has been a common thread of reviews of employment services and settlement services. David Thodey’s public service review agreed and sought to embed public delivery much more effectively in place.

The Centre for Policy Development has shown how Community Deals can do this, connecting funding sources and governance in local networks to boost economic and social outcomes, using the more efficient model recently backed by the Prime Minister for vocational education and training. The Brotherhood of St Laurence has a similar approach focused on youth unemployment.

This isn’t about choosing government over private or charitable providers, or always choosing local government as the co-ordinating authority. It’s about government getting back into the service delivery game alongside providers instead of just funding them.

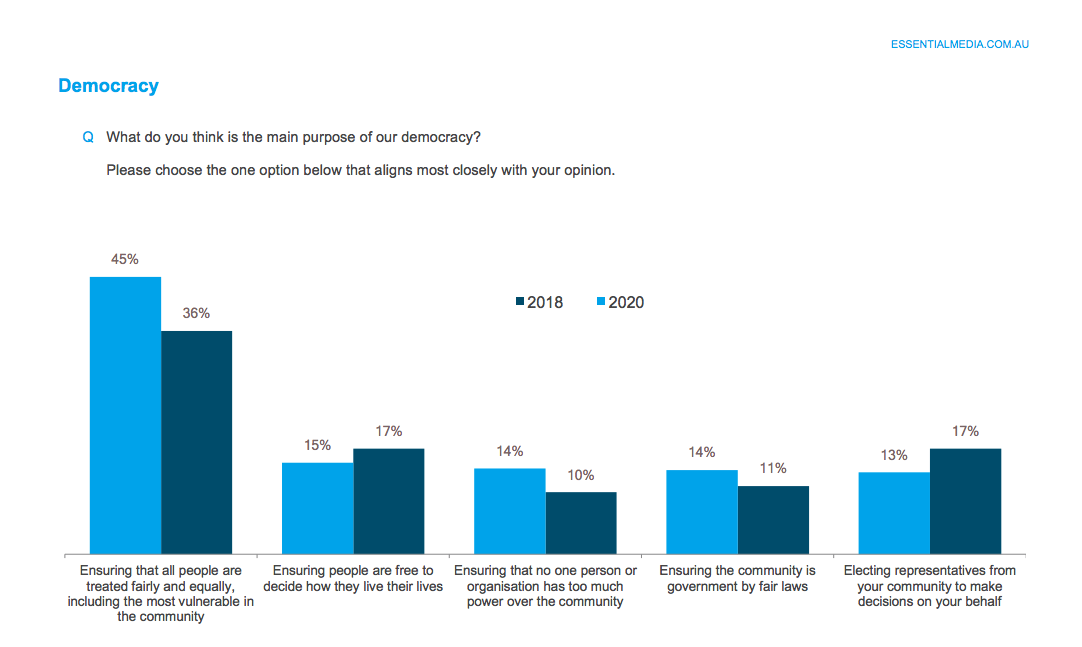

Given 90 per cent of Australians want this, it’s worth asking why. The answer may be found in our view of democracy.

Last month, we asked Australians for the third time what they think the main purpose of our democracy is. The answer now three times as popular as any other is ensuring all people are treated fairly and equally, including the most vulnerable. A total of 45 per cent of Australians chose this as the main purpose of our democracy (up from 36 per cent in 2018 and from 35 per cent in 2017), well ahead of other answers like ensuring people are free to decide how to live (15 per cent), ensuring no person or organisation has too much power (14 per cent) or electing representatives to make decisions on your behalf (13 per cent).

These figures suggest the bushfires and the virus have sharpened attitudes about our democracy and faith in government.

Australians expect government to be an active player in service delivery. And we want democracy to improve the lives of others, particularly the most vulnerable. We want that in the best of times and particularly in the worst of times. Such attitudes are instructive as governments face the biggest labour market disruption in a generation.

Fixing Jobactive to deliver during and after the pandemic cannot be achieved with new licensing contracts alone. It will take courage by governments to lead on the ground as an employer, co-ordinator, procurer, licensor and service provider. It will take honesty about how the recovery will be a grind and how we need to do clever things to make it work. More of the same is a recipe for disaster.