The health debate in Australia is all about managerialism rather than the principles that should underpin and drive a national health system. There is a great deal of movement, but the direction is not clear.

Nowhere are principles such as fairness, universality, social solidarity or citizenship mentioned by the government in its announcement of the establishment of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. The Commission is asked by the government to provide a blueprint to address ‘The rapidly increasing burden of chronic disease, the ageing of the population, rising health costs and inefficiencies exacerbated by cost-shifting and the blame game’. These are all very important issues, but do we want a well-managed and efficient system that lacks guiding principles? Do we want a high quality universal system for all, or a two-tier system with a high quality tier for the wealthy and a second, and inferior, welfare tier for the poor? Is the Government’s objective simply to manage the same set of health arrangements more efficiently than the Coalition? Does the Labor Government hold values and principles in health that differentiate it from the Coalition?

At the Centre for Policy Development we have been researching options for alternative portfolio policies, particularly in health. It quickly became clear that most of the public debate in health revolved around managerialism – efficiency, cost-pressures, productivity, cost-shifting and fragmentation – while questions about long term structure and purpose were neglected. In ‘A health policy for Australia: reclaiming universal health care’, my co-author Ian McAuley and I concluded that:

‘It is … impossible to find or even to infer any coherent set of principles in our present health policies, particularly on the issue of health care funding. Some services are provided for free, while others receive no government support. Some services are covered by tax-funded insurance, but at the same time there are incentives for people to opt out of sharing and into private insurance. Politicians talk of ‘universalism’ and a ‘commitment to Medicare’ while encouraging the development of a two-tier hospital system. Politicians talk about ‘individual responsibility’ while encouraging people to hand responsibility over to health insurance corporations. Governments, particularly Coalition governments speak vaguely about the virtues of the private sector, but only in a few areas of health care is there a degree of market competition; in general, health care has been cosseted from market forces. Labor politicians sing the praises of bulk-billing while supporting high co-payments for pharmaceuticals.’ (p.10)

In that policy paper, we set out some key principles that we believed should guide health policy design.

- A universal system accessible to all. Poor and rich should have access to the same high quality health services from the same public and private providers. We asserted that a universal system should not necessarily imply a ‘free’ system.

- Services designed around patients’ needs and not historic provider interests.

- Maximisation of individual choice. This should not be confused with the so-called ‘choice’ between look-alike private insurers.

- Fairness through universal taxpayer funding.

- Resources allocated to where they are most needed. (Not for example, to acute care and elective surgery which is promoted by the media-savvy at the expense of funding for neglected mental health sufferers.)

- The community actively involved in setting priorities.

- Technical efficiency so that we obtain the maximum benefit from our limited health dollars.

- Subsidiarity, whereby health care is delivered by the smallest or the most local health unit, subject to national policies, national funding and national standards.

These principles were set out based on our own research and extensive consultation with health policy experts. Nowhere has the government attempted to enumerate an equivalent set of principles.

This is not to say that we should be unsympathetic to governments which have to make pragmatic decisions on the basis of perceived or actual public concerns and the self-interest of entrenched vested interests. Governments can only build on what we have at the moment. But in health as in so many areas, we need some clear principles, some ‘light on the hill’ which can provide guidance and discipline in the development of our health system.

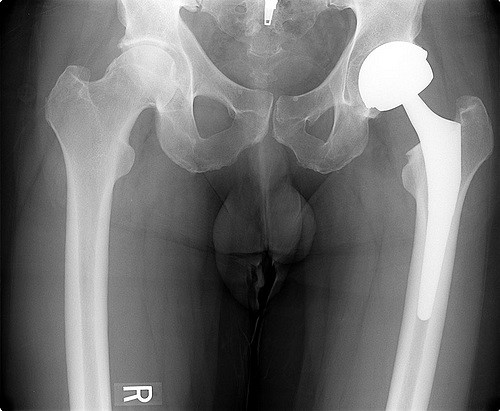

There is one area in which the government’s lack of underlying principles is most obvious. It is its commitment to continue the $6b pa government subsidy to private health insurance (PHI) that was introduced by the Howard Government. It is one thing for individuals to take out private insurance if they so desire, but it is quite a different thing for the government to subsidise mainly wealthy people to jump the queue in access to health services. The government subsidy goes overwhelmingly to the richest in our community. 80% of the top 20% of income earners in Australia have PHI. Only 20% of the poorest 20% have PHI. This $6b subsidy is the heartland of middle class welfare. PHI benefits those who seek elective surgery in metropolitan private hospitals, but disadvantages rural people who don’t have access to private hospitals. The 9% administrative costs of PHI are about double the administrative costs of Medicare, including the cost of tax collection. PHI companies do not effectively engage in cost-control. Neither do they effectively manage over-servicing in health, which is widespread in such areas as joint replacement, cataract extraction and caesarean section.

The subsidisation of PHI is threatening our universal system – as the Howard Government intended. At a point when the US government is struggling to get out of the mess that PHI has wrought in the United States, Australia is headed down the same track that the US must abandon. The government has appointed a senior executive from a major private health insurance company as the Chair of the National Health and Hospital Reform Commission. This surely signals a government retreat from universalism, the founding principle of Medicare over 30 years ago.

To justify the subsidisation of PHI, the government in its announcement of the Reform Commission spoke of ‘maximising a productive relationship between public and private sectors’. It is quite fallacious for the government to claim that subsidising private financial intermediaries like PHIs is necessary to provide a mix of public and private health delivery. Private hospitals in Australia would receive at least $1b additional each year if the PHI intermediaries were cut out of the loop and funds paid directly to hospitals. Veterans Affairs does just that. As a single public payer, it leaves it up to veterans to choose treatment in either the public or private sector. It is nonsense to suggest that financial intermediaries are necessary to support private hospitals.

To justify the subsidisation of PHI, the government in its announcement of the Reform Commission spoke of ‘maximising a productive relationship between public and private sectors’. It is quite fallacious for the government to claim that subsidising private financial intermediaries like PHIs is necessary to provide a mix of public and private health delivery. Private hospitals in Australia would receive at least $1b additional each year if the PHI intermediaries were cut out of the loop and funds paid directly to hospitals. Veterans Affairs does just that. As a single public payer, it leaves it up to veterans to choose treatment in either the public or private sector. It is nonsense to suggest that financial intermediaries are necessary to support private hospitals.

In Canada, a decade ago, the federal government established a Royal Commission to conduct a dialogue with citizens and to make recommendations to the government on an ideal health service for Canadians. The Commissioner, Dr Romanow, proposed

‘a Canadian Health Covenant that expresses Canadians’ collective vision for health care and that outlines the responsibilities and entitlements of individual citizens, health providers and governments in regard to the system. We need consensus on why the system exists, what it is intended to achieve and how its component parts should fit together. This is vital to restoring the public’s confidence in the system.’

In referring to ‘consensus on why the system exists (and) what it is intended to achieve’, Romanow was in effect saying that Canadians needed to agree on the principles that should guide the design of the Canadian health system. His report underlined the wide support amongst Canadians for the principle of universalism in health.

The Australian government has not spelt out why the Australian health system exists and what it is intended to achieve. Principles must come before managerialism.

If there is one clear but extremely worrying message that the government has given in health, it is that it is prepared to contemplate a retreat from a universal system of health care. Is that really what the government intends? More importantly, is it what Australians want?